Unmasking Synthetic Identity Fraud: A Critical Examination of Existing Guidance on Identity Fraud for Public Awareness.

How they've been getting away with it, for a long time.

Unmasking Synthetic Identity Fraud: A Critical Examination of Existing Guidance on Identity Fraud for Public Awareness. This document will continue to be updated.

Theory

The act of registering an additional identity for an individual within Companies House falls under the classification of "synthetic identity." This practice not only compromises audits and due diligence associated with individuals and their interests but also presents vulnerabilities in the broader regulatory landscape. This review delves into guidance provided by law enforcement agencies, the International Standards on Auditing, and the Companies Act of 2006. It aims to expose how the concealment of interests within synthetic identities creates loopholes in audits and provides evidence of undisclosed interests. The prevalence of public officials holding synthetic identities in Companies House directly contradicts the Nolan Principles of openness and transparency, necessitating a thorough investigation by law enforcement.

Introduction

This report evaluates guidance issued by the UK Government and law enforcement agencies concerning identity fraud. It consolidates definitions related to various identity fraud methods from entities such as the Cabinet Office, Government Data Services, National Cyber Security Centre, Financial Conduct Authority, Action Fraud, the City of London Police, International Standards on Auditing, and Companies House. The gap analysis is conducted on these organisations to identify discrepancies, omissions, and inconsistencies in their respective approaches to combating identity fraud

The evidence presented underscores conspicuous gaps in guidance and International Standards of Accounting protocols, creating an environment where identity fraud committed by public officials and company directors can elude the scrutiny of accountants and auditors. The report brings to light how directors employ synthetic identities, crafted within Companies House, to deceive those entrusted with ensuring lawful business practices.

Exploration of gaps, omissions, and inconsistencies in the government's response to identity fraud forms the core of this report. It emphasises how identity fraud breaches cybersecurity principles founded on the uniqueness of individual identities and scrutinises the evolution of law enforcement frameworks in response to identity fraud.

Method

The report relies on definitions and facts primarily sourced from information published by the UK Government on identity fraud. It identifies gaps in definitions, inconsistencies in usage, and actions to address synthetic identity fraud—a common method that warrants attention. The objective is to test the legal principle that individuals, by registering multiple identities in Companies House and failing to disclose all their interests, engage in synthetic identity fraud, rendering them unsuitable for public office. Case studies are included to demonstrate the use of synthetic identities and the deception they enable.

Limitations:

Manual Search Methodology: The investigation primarily relied on manual searches involving a visual examination of results returned by search inquiries. This method poses a medium risk of omitting information available from regulatory bodies that may not be easily visible through manual searches.

Dependency on Publicly Available Data: The analysis is contingent upon publicly available data up to February 2024. Limitations may arise from the absence of access to subscription sites, databases, or real-time information, potentially overlooking updates or recent developments.

Potential Missed Identities: Searches for multiple identities are inherently manual, and there is a risk of overlooking additional identities, particularly if they involve false dates of birth or entirely different names. Visual searches may not capture all relevant details, potentially leading to omissions.

Regulatory Information Access: There may be pertinent information held by regulatory bodies that was not accessible during the manual search process.

Legal Considerations: The report does not provide legal advice, and individuals should seek legal counsel for appropriate guidance on handling findings related to identity fraud. Legal processes and implications may vary based on jurisdiction and the nature of the identified issues.

Interpretation of Fraud Indicators: The identification of synthetic identity fraud and associated fraudulent activities involves interpretation of available data. While efforts have been made to align findings with existing legal frameworks and guidance, interpretations may vary.

Keywords: Cabinet Office, Government Digital Services, Companies House, Financial Reporting Council, International Standards on Auditing, Financial Conduct Authority, Action Fraud, Deduplication, Synthetic identities, Clone firms.

Analysis

1. UK Cabinet Office and Government Digital Services guidance.

The guidance provided by the UK Cabinet Office and Government Digital Services on “How to prove and verify someone's identity” is a critical resource in understanding the complexities of identity verification. The document covers a range of topics, including the definition of identity, when and why identity checks are essential, and how to perform these checks effectively. It establishes the importance of checking someone's identity in light of the increasing instances of identity fraud and provides pertinent definitions crucial for developing the argument.

The section "Why you should check someone’s identity" underscores the rising threat of identity fraud, listing motives such as unauthorised access to services, benefit fraud, personal data theft, and aiding organised crime. Particularly noteworthy is the emphasis on synthetic identities, whether entirely fictional or constructed based on a real identity. The example of using a false date of birth to access a gambling site illustrates the concept of synthetic identity, even when other details remain accurate. See image 1, below:

Definitions quoted from “How to prove and verify someone's identity”.

An identity is a combination of ‘attributes’ (characteristics) that belong to a person.

A claimed identity is a combination of information (often a name, date of birth and address) that represents the attributes of whoever a person is claiming to be.

You could be affected by identity fraud if you do not check someone’s identity. This includes being targeted by someone: using a ‘synthetic’ (made up) identity, or who is pretending to be someone else (an ‘impostor’).

Synthetic identities can be fictional or based on a real identity. For example, someone who gives a false date of birth to access a gambling site is using a synthetic identity, even if their other details are correct.

Compared to not doing any identity checks, having low confidence in someone’s identity will lower the risk of you accepting either: synthetic identities or impostors who do not have a relationship with the claimed identity (Cabinet Office and Government Digital Service Guidance, How to prove and verify someone's identity).

Types of identity fraud are delineated into two main categories: fraud involving a 'synthetic' identity (either entirely fictional or based on a real identity) and fraud perpetrated by an 'impostor' posing as someone else. The guidance's scenario involving an individual using authentic details but altering their date of birth to access a gambling site serves as a pertinent example of a self-created 'synthetic identity' rooted in the individual’s real identity.

Drawing parallels, it is posited that the concept of 'synthetic identity' within the guidance aligns with instances in Companies House where individuals alter attributes such as name spelling, date of birth, or residential address to create a second identity. Thus, the term 'synthetic identity' aptly characterises duplicated identities within Companies House, often created with the intent to establish a new identity by providing a different set of attributes.

It's acknowledged that errors might lead to the unintentional creation of a second identity, and there are processes in place to rectify such mistakes. The crucial test lies in whether the individual declares all their interests associated with all their identities, indicating whether it was created accidentally or deliberately to conceal interests. This recognition becomes a pivotal point in understanding the motivations behind identity creation within Companies House and establishes the need for a thorough examination of declared interests.

2. National Cyber Security Centre.

The National Cyber Security Centre provides guidance on the design principles and requirements for unique identities to operate trustworthy, zero trust systems, which are foundational for cyber security:

A zero trust architecture is an approach to system design where inherent trust in the network is removed, Introduction to Zero Trust - NCSC.GOV.UK.

An identity can represent a user (a human), service (software process) or device. Each should be uniquely identifiable in a zero trust architecture. This is one of the most important factors in deciding whether someone or something should be given access to data or services.

User identity: Your organisation should use a definitive user directory, creating accounts that are linked to individuals. This could come in the form of a virtual directory or directory synchronisation, to give the appearance of a single user directory. (NCSC Zero trust architecture design principles, Know your user, service and device identities - NCSC.GOV.UK

A false non-match occurs when an individual's biometric characteristic appears not to match their own previously collected biometric characteristic. In a de-duplication system, this can result in the undesired creation of a second record for the individual. The false non-match rate is: A measure of the propensity of the system to make this error.

These unique identities are one of a number of signals that feed into a policy engine, which uses this information to make access decisions. For example, a policy engine could evaluate user and device identity signals to determine if both are genuine, before allowing access to a service or data (Biometric recognition and authentication systems), Measuring performance - NCSC.GOV.UK.

Biometric systems have the ability to check against and consolidate multiple records referring to the same individual. This can help with database de-duplication and in the elimination of fraudulent registrations, Understanding biometrics - NCSC.GOV.UK (page 2).

User identity. Your organisation should use a definitive user directory, creating accounts that are linked to individuals.

“Considering the risks in any system is fundamental”, Introducing component-driven and system-driven risk... - NCSC.GOV.UK

The guidance provided by the NCSC is directly applicable to Companies House, considering its de-duplicated system. Records within Companies House are associated with the same identity when the biometric data (name, date of birth, and residential address) aligns. Importantly, any variation in these attributes can result in the “undesired creation of a second record for the individual”. Notably, the NCSC fails to explicitly give this “second record” a name. Given that it is based on an individual's real identity, it is apt to call it a synthetic identity.

The omission of this nomenclature detracts from the significance of recognising these duplicates as enablers for concealing interests. The nomenclature is critical in highlighting the role of these duplicates in facilitating identity-based concealment, aligning with the broader discussions on identity fraud and the potential misuse of multiple identities.

3. Financial Conduct Authority: Clone firms and individuals.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) does not refer to “synthetic identities” or “imposters”. However, it uses the term “clone individuals” and describes “clone firm” fraud. It has a webpage dedicated to fraud committed by Clone firms and individuals. This is copied below, image 2.

The FCA page on “Clone firms and individuals” describes a situation where an individual pretends their firm is related to a legitimate firm:

They'll often use the name and address of a genuine firm, or they may copy the firm reference number (FRN).

They may also:

copy the website of an authorised firm, making small changes (for example, to the phone number)

point you to the genuine firm’s website, but use different details to contact you

give you the details of a genuine firm but give you the wrong phone number

use email addresses that look similar to the genuine firm’s or use providers such as Outlook or Gmail

They may even claim that a firm's contact details on the FS Register are out of date.

The FCA recommends checking the FS register and checking the firm’s details:

on the firm’s website

with directory enquiries

This is helpful, but it fails to provide guidance on how to use Companies House to identify clone firms and synthetic identities that are registered there.

Omission of clone firm fraud perpetuated by a director of the legitimate firm.

The FCA does not draw attention to the fact that the individual, themselves, might be the one perpetrating the fraud, what the Cabinet Office describes as synthetic identity fraud based on a real identity. Setting up a second company with a similar name to their legitimate company, to divert funds to, from the legitimate company that they “report" as their only interest, is one of the oldest tricks in the book. It is surprising that attention is not drawn to this method of identity fraud which is used by directors to defraud their co-directors, shareholders and HMRC.

The due diligence analysis underpinning this report makes use of firms’ websites, Companies House, regulatory authorities and the Government Contracts Database.

The FCA describe clone firm fraud:

Fraudsters are always looking for new ways to scam the public. One of these involves pretending to be from firms we authorise. We call this a clone firm.

The FCA gives a more detailed description of Clone firm fraud in its A to Z of financial terms:

Fraudsters sometimes claim to be from genuine firms authorised by us. They may use details, such as the names and addresses of authorised firms or individuals, and 'firm reference numbers' (FRN) to suggest they're genuine. Find out more about clone firms and how to protect yourself from scams.

The link, on the A to Z of financial terms page, for “clone firms” redirects to the first page shown for “clone firms and individuals”, in image 1.

The FCA omit to define “clone individuals”

The FCA do not define “clone individuals” on the “Clone firms and individuals” webpage, even though it is part of the title of that page.

A search on the FCA website locates just one example of cloned individual, see image 2 (a search of clone individual presents similar results).

There is one search result with the words “cloned individual”. The other results refer to clone firms. Entering into the first record for a cloned individual, first published: 15/12/2011, presents the information, in image 3.

In this example (image 3) an individual calling themselves Chris Ellis-Keeler, is purporting to be Christopher John Ellis-Keeler who is a genuine FCA approved individual.

FCA authorised individual details

This genuine individual has no association whatsoever with the ‘cloned individual’. He is authorised to offer, promote or sell financial services or products in the UK:

The link to “cloned individuals”, on the record in image 3, an example of cloned individual, redirects to the “cloned firms and individuals” page, image 1. There is no further information about cloned firms and individuals and how they are used to commit fraud. Testing other key words, to describe this sort of fraud, the FCA do not define business or individual identity fraud. Nor does the FCA use the term synthetic identity fraud.

Case study 1. MoneyFarm.

Extracts from a due diligence report, HMRC and Moneyfarm Chair, Dame Jayne-Anne Gadhia, has twelve identities in Companies House. Part 2.

Financial Conduct Authority record for MFM Investment Ltd provides a notice that “Money Farm” is a “cloned firm” and “part of a scam”.

Referring to the Financial Conduct Authority register, the record relating to MFM Investment Ltd were located in a search of the Financial Services Register. There are 14 companies returned in the search on “MFM”, one of these is MFM Investment Ltd. This record provides the following information:

MFM Investment Ltd Reference number: 629539 Address information 90-92 Pentonville Road London N1 9HS UNITED KINGDOM Website ww.moneyfarm.com Companies House number information 09088155

There is a “Notice” on the MFM Investment Ltd record in the FS Register, which warns:

Clones of this firm

Individuals are using the details of this firm to suggest they work for the genuine firm. We call this a cloned firm and it is typically part of a scam.

To contact the genuine firm you should call the switchboard number listed on the Register - and contact us if it is not provided. Find out more about the clone firm(s):

Money Farm (Clone of FCA Authorised Firm)

Added to the FS Register on 05 May 2023.

The FCA, since 5 May 2023, have published a “Notice” which warns that individuals from “Money Farm” are suggesting that they work for MFM Investment Ltd, that “Money Farm” is a “cloned firm” and “part of a scam”. To find out more information, the record for this firm is accessed by clicking on its name. This returns:

Money Farm (Clone of FCA Authorised Firm)

This is an unauthorised firm that uses the details of a genuine FCA-regulated firm when offering products and services. This makes the unauthorised firm appear as if it is regulated. We strongly suggest you do not deal with unauthorised firms.

Unauthorised

Note that this Money Farm record, on the FS Register, does not provide: a company number for “Money Farm”, details of any individuals, or a registered address.

The Financial Conduct Authority warn that a clone company is impersonating “Moneyfarm” and I found five potential candidates. The Money Farm Limited, also known as The Moneyfarm Limited, is a certain clone, as evidenced by its record in the Financial Services Register and described in the following image:

“Moneyfarm” impersonation.

The FS register record for The Money Farm Limited provides a website link to MFM Investment Limited’s “Moneyfarm”; the use of the registered address of Associated Trading Limited, which ensures that any correspondence, such as an invoice or payment, would be sent to Mr Voegt; and, any check on the company registration number in Companies House which will confirm that Mr Voegt was a director of The Moneyfarm Limited, relying on any reviewer to dismiss the fact that the names don’t match. This record, even though The Money Farm Limited is flagged as “No longer authorised”, could be used in “know your customer” checks to support a transaction, today, in the name of William Voegt at The Money Farm Limited or The Moneyfarm Limited, that was intended for MFM Investment Ltd’s “Moneyfarm”. With or without the complicity of a director of MFM Investment Ltd, contracts intended for “Moneyfarm” could be diverted to The Moneyfarm Limited, using the Financial Services record, as proof of identity. This record holds the components that can enable Mr Voegt to impersonate that he is a director of “Moneyfarm”.

Clone firm fraud can occur in any industry and the methods can vary by industry. The focus, above, is on clone financial services firms and other companies impersonating them. It could have included company directors holding clone companies of their own firm, for the purposes of diverting funds. There are other methods of clone fraud that the Financial Conduct Authority references but it fails to define cloned individual fraud.

4. Action Fraud

Anyone wishing to report fraud is directed to Action Fraud. Action Fraud is the UK’s national reporting centre for fraud and cyber crime. The service is run by the City of London Police, which is the national policing lead for economic crime. The website explains their role:

ACTION FRAUD

Action Fraud is the UK’s national reporting centre for fraud and cyber crime where you should report fraud if you have been scammed, defrauded or experienced cyber crime.

Information related to search terms “Synthetic”, “identity fraud” and “cloned firm”.

A search on the Action Fraud website on the term “synthetic” returns no results.

Searching using the term “identity fraud” returns articles that provide limited dispersed information, see image:

The first article listed, published 01-07-2015, is nine years old Alert: Scammers ordering bank cards in victim’s names by intercepting mail | Action Fraud.

The MoneySavingExpert gives identity fraud protection advice | Action Fraud was published 02-07-2010 and it fails to describe the different methods of identity fraud.

A search on the term “cloned firm” returns just one entry, see image.

This is:

Attack of the clone firms: over £78 million stolen in 'clone' firm investment scams | Action Fraud (banner reproduced below).

This article includes the following information:

What is a ‘clone firm’ investment scam?

‘Clone firms’ are set up by fraudsters using the name, address and ‘Firm Reference Number’ (FRN) of real companies authorised by the FCA.

This provides the headlines:

Number of ‘clone firm’ investment scams reported increased by 29% as UK went into first lockdown

Victims scammed out of more than £45,000 each, on average

77% of investors do not know or are unsure what a ‘clone investment firm’ is

FCA and Action Fraud advise investors to only use contact details on the FCA Register to help avoid ‘clone firm’ scams

This information shared by Action Fraud, omits that it’s not only investment firms that can be involved in clone firm fraud. This article also omits to discuss “cloned individuals”, which the Financial Conduct Authority also fails to expand upon, and it omits synthetic identity fraud.

5. City of London Police advice relating to identity fraud.

A search on “identity fraud” on the City of London Police website, Search - identity fraud | City of London Police, returns the following screen:

Opening the “Identity fraud” link provides this information:

The City of London Police provide the following definition of identity fraud:

Identity fraud

Identity fraud, or ‘ID theft’, involves the use of a person’s stolen details to commit crime. Many victims never find out exactly how someone got hold of their details, and clearing things up afterwards can be costly and stressful.

The City of London Police webpage gives advice relating to:

Links, attachments, suspicious emails

Be mindful of what you share online

Passwords and two-factor authentication (2FA)

Review your bank statements regularly

The City of London Police refers to just one aspect of potential identity fraud, “imposter fraud”, as defined by the Cabinet Office and Government Data Services guidance. They fail to include fraud conducted by individuals using multiple identities of themselves, ie synthetic or clone identity fraud.

Corporate Fraud

The City of London Police introduce different terminology relating to corporate fraud, “Company impersonations or corporate identity fraud”.

Corporate-related identity, long/short firm and insolvency fraud | City of London Police

The City of London Police provide the following definition:

Company impersonations or corporate identity fraud

“If someone calls claiming to be from a company that you have a business relationship with and you’re suspicious about the call or the caller’s identity”.

This refers to an external individual, purporting to represent a firm that it is not associated to.

Company hijack

Company hijacks normally involve fraudsters changing the details of company directors and registered offices.

Long and short firm fraud

This is when criminals hijack or set up an apparently legitimate business to defraud both its suppliers and customers.

They’re happy to deal in any goods or services with a market value, preferably if they’re untraceable and easily disposable, such as electrical goods, toys, wine, spirits and confectionery.

An example of long firm fraud

Your business has a relationship with a company that has a good reputation and credit history. The company places lots of small orders with you, paying promptly. You trust this company as a supplier.

The company changes its activity, though, and makes much larger orders with you. You supply your goods but the company disappears without paying you and sells the goods on.

Examples of short firm fraud

Your company supplies to a new business. If it’s a limited company, it may have filed several sets of false accounts and director appointments at Companies House within a short space of time. It may also provide false trade references to look credit-worthy.

The company has no day-to-day trading activity. It gets goods from your business on credit, which are delivered to third-party addresses. Again, the company disappears without paying you and sells the goods on for cash.

The City of London Police introduce different terminology again, “company impersonations” and “corporate identity fraud”, which relate to clone company fraud, conducted by an internal or external agent. The cases considered on the website describe an external agent conducting fraud against a subject. The City of London Police fail to consider fraud perpetrated by directors creating clones of their own legitimate company.

6. Thomson Reuters on Synthetic identity fraud

Thomson Reuters reported, on 21 April 2023, in Trends in synthetic identity fraud that, without providing a source for the figures:

No one knows precisely how much money is lost to synthetic identity theft — estimates range from $20 to $40 billion and growing — but one thing is certain: criminals know opportunity when they see it. Synthetic identity scams have been so successful in so many ways that they are now being used to facilitate all sorts of criminal activity, including romance scams, money laundering, illegal arms sales, human trafficking, and terrorism. (…) If synthetic identity fraud were only committed by a few unscrupulous individuals, it wouldn’t be such a huge problem. But the truth is that well-organized gangs worldwide are committing synthetic identity fraud(.)

This article provides an overview of synthetic identity scams, highlighting its rapid growth and exploitation of vulnerabilities in various sectors. The risk from identity fraud is significant as it includes “money laundering, illegal arms sales, human trafficking, and terrorism”. However, the article overlooks individuals creating multiple identities in corporate registries, a significant aspect enabling fraud and non-disclosure of interests. This omission limits the article's completeness, emphasising the need for a broader perspective on synthetic identity fraud encompassing corporate practices and their impact on financial transparency and compliance. Thomson Reuters’ fails to provide a source for the data described.

7. What does the International Standard on Auditing relating to fraud say?

International Standard on Auditing (UK) 240 (ISA 240 (UK)) deals with the auditor's responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements. Excepts below are directly relevant to the auditors’ duty to identify risks associated to fraud:

Scope of ISA 240 (UK): Auditor's responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements

1. This International Standard on Auditing (UK) (ISA (UK)) deals with the auditor's responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements. Specifically, it expands on how ISA (UK) 315 (Revised July 2020) [Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement] and ISA (UK) 330 (Revised July 2017) [The Auditor's Responses to Assessed Risks] are to be applied in relation to risks of material misstatement due to fraud.

Characteristics of Fraud

2. Misstatements in the financial statements can arise from either fraud or error. The distinguishing factor between fraud and error is whether the underlying action that results in the misstatement of the financial statements is intentional and involves deception or is unintentional.

3. Although fraud is a broad legal concept, for the purposes of the ISAs (UK), the auditor is concerned with fraud or suspected fraud that causes a material misstatement in the financial statements. Two types of intentional misstatements are relevant to the auditor – misstatements resulting from fraudulent financial reporting and misstatements resulting from misappropriation of assets. (ISA 240 (UK)).

4. The primary responsibility for the prevention and detection of fraud rests with both those charged with governance of the entity and management. […]

Responsibilities of the Auditor

5. An auditor conducting an audit in accordance with ISAs (UK) is responsible for obtaining reasonable assurance that the financial statements taken as a whole are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error. […]

6. As described in ISA (UK) 200 (Revised June 2016), the potential effects of inherent limitations are particularly significant in the case of misstatement resulting from fraud. The risk of not detecting a material misstatement resulting from fraud may be higher than the risk of not detecting one resulting from error. This is where fraud may have involved sophisticated and carefully organized schemes designed to conceal it, such as forgery, deliberate failure to record transactions, or intentional misrepresentations being made to the auditor. Such attempts at concealment may be even more difficult to detect when accompanied by collusion. Collusion may cause the auditor to believe that audit evidence is persuasive when it is, in fact, false. The auditor's ability to detect a fraud is affected by factors such as the skillfulness of the perpetrator, the frequency and extent of manipulation, the degree of collusion involved, the relative size of individual amounts manipulated, and the seniority of those individuals involved. While the auditor may be able to identify potential opportunities for fraud to be perpetrated, it may be difficult for the auditor to determine whether misstatements in judgment areas such as accounting estimates are caused by fraud or error.

8. When obtaining reasonable assurance, the auditor is responsible for maintaining professional skepticism throughout the audit, considering the potential for management override of controls and recognizing the fact that audit procedures that are effective for detecting error may not be effective in detecting fraud. The requirements in this ISA (UK) are designed to assist the auditor in identifying and assessing the risks of material misstatement due to fraud and in designing procedures to detect such misstatement.

Related Parties

15-1. In obtaining audit evidence regarding the risks of material misstatement due to fraud the auditor shall comply also with the relevant requirements in ISA (UK) 550.

The audit evidence, required to assure compliance that all related parties and related party transactions are identified as such, is so significant that it has its own International Standard on Auditing, ISA (UK) 550 Related Parties (Effective for audits of financial statements for periods ending on or after 15 December 2010).

ISA (UK) 550 is dedicated to “Related Parties” and it clearly states the issues that auditors must address and gives some examples of fraud for auditors to take into consideration when designing their audit.

Section A19 focuses on the significant risk of management override of financial reporting controls to enable fraudulent transactions with related parties that have not been disclosed (bold is used to draw your attention to text that I will build on).

A19. Fraudulent financial reporting often involves management override of controls that otherwise may appear to be operating effectively. For example, management's financial interests in certain related parties may provide incentives for management to override controls by (a) directing the entity, against its interests, to conclude transactions for the benefit of these parties, or (b) colluding with such parties or controlling their actions. Examples of possible fraud include:

Creating fictitious terms of transactions with related parties designed to misrepresent the business rationale of these transactions.

Fraudulently organizing the transfer of assets from or to management or others at amounts significantly above or below market value.

Engaging in complex transactions with related parties, such as special-purpose entities, that are structured to misrepresent the financial position or financial performance of the entity. […]

In my opinion, an example that should be included in A19, is:

Duplicated firm or officer registrations in Companies House create cloned entities and synthetic identities, which are fictitious. These have been used to enable transactions with related parties, that are concealed from the auditor and due diligence software. To minimise this risk, refer to Companies House, and to the company registers of other countries, to test whether duplicate / clone / synthetic / multiple identities are registered. Interests held in these identities are related parties that require considering for related party transactions.

The ISA (UK) 550 highlights “Maintaining Alertness for Related Party Information When Reviewing Records or Documents” and provides a list of records that an auditor can/should inspect.

Records or Documents That the Auditor May Inspect (Ref: Para. 15)

A22. During the audit, the auditor may inspect records or documents that may provide information about related party relationships and transactions, for example:

Third-party confirmations obtained by the auditor (in addition to bank and legal confirmations).

Entity income tax returns.

Information supplied by the entity to regulatory authorities.

Shareholder registers to identify the entity's principal shareholders.

Statements of conflicts of interest from management and those charged with governance.

Records of the entity's investments and those of its pension plans.

Contracts and agreements with key management or those charged with governance.

Significant contracts and agreements not in the entity's ordinary course of business.

Specific invoices and correspondence from the entity's professional advisors.

Life insurance policies acquired by the entity.

Significant contracts re-negotiated by the entity during the period.

Reports of the internal audit function.

Documents associated with the entity's filings with a securities regulator (for example, prospectuses).

A22 omits to specify Companies House. In my opinion, the first point in this list should read: A22: 1. Records in Companies House that relate to the entity and the firm’s officers and any potential duplicate entity registrations.

A23 requires the auditor to use professional scepticism to look for undisclosed related parties.

A23. Examples of arrangements that may indicate the existence of related party relationships or transactions that management has not previously identified or disclosed to the auditor include:

Participation in unincorporated partnerships with other parties.

Agreements for the provision of services to certain parties under terms and conditions that are outside the entity's normal course of business.

Guarantees and guarantor relationships.

A23 omits to highlight “Undisclosed incorporated partnerships, including those held in multiple identities of officers of the firm, registered in Companies House.”

A25 gives examples of the sort of transactions that are vulnerable to fraud.

A25. Examples of transactions outside the entity's normal course of business may include:

Complex equity transactions, such as corporate restructurings or acquisitions.

Transactions with offshore entities in jurisdictions with weak corporate laws.

The leasing of premises or the rendering of management services by the entity to another party if no consideration is exchanged.

Sales transactions with unusually large discounts or returns.

Transactions with circular arrangements, for example, sales with a commitment to repurchase.

Transactions under contracts whose terms are changed before expiry.

A25 would be strengthened with the inclusion of transactions involving related parties with which name switching has occurred, for example, Qinetiq Group plc and Qinetiq Holdings Limited, which are companies that have switched names.

Present International Standards on Auditing have a “blind spot” regarding individuals and companies with multiple identities.

Presently, auditing standards and protocols do not include consideration of the possibility that other identities for an individual, or a company, may exist. ISA 240 (UK) omits any consideration of keywords associated to this method of fraud; multiple identities, identity fraud, duplicate, synthetic identity, and, clone identity. Therefore, any interests held in other identities, unless the director explicitly declares them to the auditor, would remain unknown and any related party transactions would not be monitored, as required for accountability and to minimise associated risks of criminal activity.

If a director or secretary does declare an interest, whether it is held in another identity, or not, it is logged in the company’s register of interests. If an interest is not in the register of interests, and can be proven to exist, then it has failed to be declared in the register of interest and this is a criminal offence.

The concealment of interests that have failed to be declared is perpetrated in order to misappropriate assets, and reduce tax and dividend pay-outs. The effect is material misstatements in the financial reporting. These are the characteristics of fraud that are described by ISO 240 (UK) stipulating auditor's responsibilities relating to fraud in an audit of financial statements. However, the ISO neither references this method of fraud nor provides a protocol that would expose it.

8. The Companies Act 2006

The risk to the public is that interests concealed in other identities are unknown to an auditor, or due diligence software, and they remain unconsidered for; conflict of interests, mutual interests, segregation of duties, related party transactions, and “Know Your Customer”, “Know Your Supplier” analysis, etc.. This breaches the Fraud Act 2006 and Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing legislation and puts the public at risk of fraud, terrorism financing, people trafficking and money laundering.

The Companies Act 2006 gives a company a wide range of powers and duties, depending on their “nature of business”. The public rely on auditors and the regulators to ensure that there are no material misstatements or misappropriation of assets. The public trust that compliant audits and the regulator ensure that a firm’s purpose does not conflict with the public’s best interest. However, an individual holding multiple identities fundamentally breaches the present measures that ensure transparency, accountability and legality. Multiple identities compromise all audits and due diligence associated with the person, since the creation of their second identity, and put the public at serious risk of firms’ misuse of powers derived under the Companies Act 2006.

The creation of a synthetic identity, combined with non-disclosure, breaches several provisions of the Companies Act 2006, specifically, but not exclusively, the following sections:

Particulars of directors to be registered: individuals including name and any former name and date of birth, Section 163. [Applicable when a different version of the individual’s name has been registered]

Register of directors' residential addresses, Section 165.

Notifying the registrar within 14 days of any change in its register of directors or of directors' residential addresses, Section 167.

A person who ceases to be a director continues to be subject to the duty to avoid conflicts of interest, Section 170 (2).

Duty to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence, Section 174.

Duty to avoid direct or indirect conflicts of interest, Section 175.

Duty to declare interest in proposed transaction or arrangement, Section 177.

Declaration of interest in existing transaction or arrangement, Section 182.

Disclosure to auditors that there is no relevant audit information of which the company's auditor is unaware. A person guilty of this offence is liable to imprisonment, Section 418.

Allocation of unique identifiers, Section 1082, when a person has established more than one unique identifier in Companies House by varying their name, date of birth or usual residential address in the register.

The Corporate Prosecutions Annex A: Companies Act 2006, Schedule of Company Offences, does not include entries for these breaches with the exception of section 167.

In order to monitor conflicts of interest, it is important that a person's history in Companies House is associated to a unique identity for on-going assurance. Multiple identities can enable breaches of Section 175 and 170, because it enables interests to be concealed. Section 170 is an important provision, as it indicates that the obligation to avoid conflicts persists even after a person ceases to hold the directorial position.

Establishment of Precedence for Prosecuting Breaches of the Companies Act 2006

The Corporate Prosecutions Annex A: Companies Act 2006, Schedule of Company Offences, lacks entries for several breaches, including Section 1082, which mandates unique identifiers for individuals within Companies House records. Notably, prosecutions for such breaches have not been pursued, setting a concerning precedent.

Background: Section 1082 of the Companies Act 2006 requires individuals to maintain a single unique identifier within Companies House records. Breaches of this provision compromise the accuracy and integrity of corporate records, potentially facilitating fraudulent activities and undermining regulatory oversight.

Current Situation: Despite clear breaches of Section 1082 and other relevant provisions of the Companies Act 2006, prosecutions for such offences have not been initiated. This lack of enforcement undermines the regulatory framework governing corporate governance and fosters a culture of non-compliance.

Importance of Precedence: Establishing precedence for prosecuting breaches of the Companies Act 2006, including Section 1082, is essential to uphold the rule of law and ensure accountability within the corporate sector. Without consequences for non-compliance, there is a risk of systemic disregard for regulatory requirements, compromising the integrity of corporate governance.

Recommendations:

Initiate Prosecutions: Relevant authorities should prioritize the prosecution of breaches under the Companies Act 2006, including offences related to unique identifiers within Companies House records.

Enhance Regulatory Oversight: Implement measures to strengthen regulatory oversight and enforcement mechanisms to prevent future breaches and promote compliance with corporate governance regulations.

Raise Awareness: Educate stakeholders about the importance of compliance with the Companies Act 2006 and the consequences of non-compliance to foster a culture of accountability and transparency within the corporate sector.

Conclusion: Prosecuting breaches of the Companies Act 2006, including Section 1082, is imperative to uphold the integrity of corporate records and maintain public trust in the regulatory framework governing corporate governance. By establishing precedence for enforcement actions, authorities can deter future non-compliance and safeguard the interests of stakeholders in the corporate sector.

Companies House guidance on synthetic identity fraud.

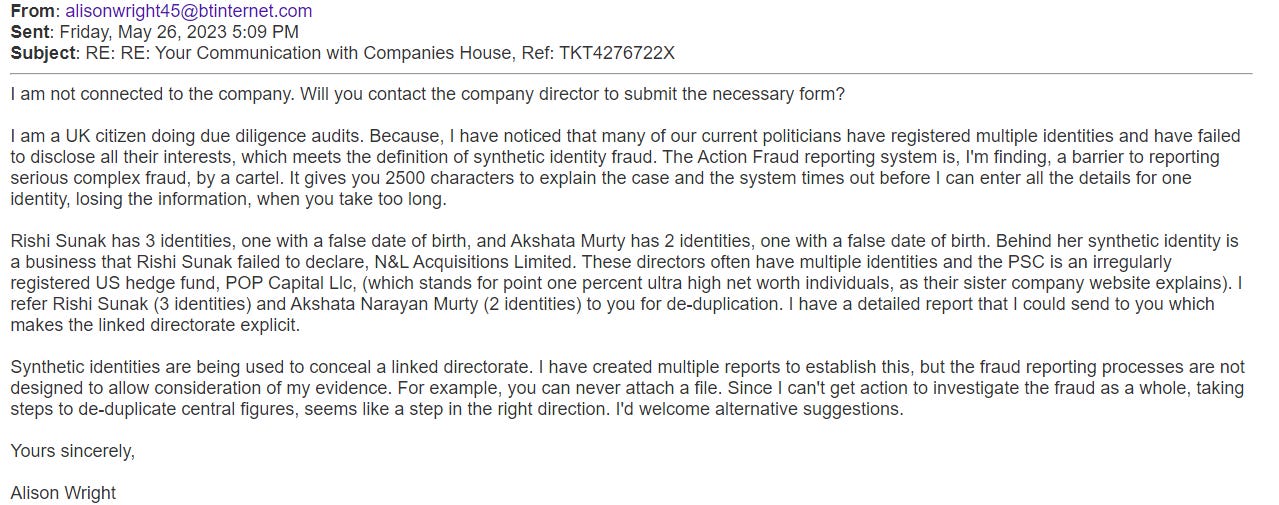

Companies House guidance makes no reference to synthetic identities or identity fraud, although it specifies that an individual should have one unique in Section 1082. This is a fundamental assumption upon which our auditing standards are derived. To illustrate the Companies House response to the issue of individuals holding synthetic identities, below is a copy of my communication with Companies House, in response to my email (reformatted, below for readability) sent Sunday, May 14, 2023 7:46 AM:

Dear Companies House enquiries team,

These two identities for Peter Howard (born August 1947) have the same address and, therefore, belong to the same person. Please will you de-duplicate these records?

Peter HOWARD personal appointments

Peter HOWARD Total number of appointments 1 Date of birth August 1947

ADVANCED CHAIN TECHNOLOGIES (EUROPE) LIMITED (04098020)

Company status Active

Correspondence address Advanced Chain Technologies (Europe) Ltd., Highgrounds Road, Worksop, Nottinghamshire, England, S80 3AT

Role ACTIVE Director Appointed on 27 October 2000 Nationality British Country of residence Australia Occupation Mechanical Engineer

and Peter HOWARD personal appointments

Peter HOWARD Total number of appointments 1 Date of birth August 1947

WALKWORTH FARM LIMITED (10576637)

Company status Active

Correspondence address C/O Advanced Chain Technologies (Europe) Ltd, Highgrounds Way, Rhodesia, Worksop, Nottinghamshire, United Kingdom, S80 3AT

Role ACTIVE Director Appointed on 23 January 2017 Nationality British,Australian Country of residence England Occupation Mechanical Engineer

Yours sincerely

Alison Wright

The response from Companies House is copied below:

.

My response:

And the reply:

Establishing multiple identifiers (identities) in Companies House.

Companies House creates an unique identifier (identity) based on three attributes:

When our system associates appointments it tries to determine if it's the same person by analysing the following details:

The Officer Name

Date of Birth

Usual Residential Address (URA)

Unless all the above criteria are met and the information is deemed to be consistent, the appointments will remain separate.

Companies House authority and duty to merge duplicate records:

Companies House does have an authority and duty to merge duplicate records when it is brought to our attention. (Registrars Functions case worker, Companies House, 26 May 2023)

Since I am not connected to the firm, and I am pointing out a fraudulent registration, the case worker recommends that I report this to Action Fraud. My response shows why this is not a suitable route forward. The conversation continues:

After a prompt, I was resent the boilerplate text that was previously sent on 19/3/23.

The email correspondence with Companies House (CH) reveals a nuanced landscape surrounding the detection and handling of synthetic identities within their systems. While the communications acknowledge CH's authority and duty to de-duplicate records when brought to their attention, they underscore the necessity for confirmation of the inquirer's connection to the company before initiating any changes. This requirement introduces a layer of procedural complexity, particularly for independent auditors or concerned citizens engaging in due diligence and it results in no action being taken.

The definition of synthetic identities, as outlined in the Cabinet Office and Government Digital Services guidance, plays a pivotal role in the discourse. The guidance, highlighting the risks associated with synthetic identities, emphasises the importance of thorough identity checks to mitigate potential fraudulent activities.

The National Cyber Security Centre's (NCSC) guidance on zero-trust architecture and unique identities contributes a crucial layer to the analysis. It introduces the notion of false non-matches and the inadvertent creation of a second record for an individual due to variations in key attributes. Despite the recognition of this occurrence, the NCSC guidance lacks specific nomenclature for these duplicates, such as synthetic identities or cloned identities, potentially diminishing the clarity of their significance.

The email chain reveals a challenge in terminology and classification within the processes of CH and related cybersecurity guidance. The absence of explicit terms like "synthetic identity" or "cloned identity" in certain contexts might hinder a comprehensive understanding of the magnitude of the issue, potentially impacting the effectiveness of remedial actions.

The INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ON AUDITING (UK) 240 (REVISED MAY 2021) (updated May 2022) (ISO 240) lays out the “Auditor's Responsibilities Relating to Fraud in an Audit of Financial Statements”. The standard is published by the Financial Reporting Council, which describes, on page 2:

The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) is the UK’s independent regulator responsible for promoting responsible for promoting transparency and integrity in business. The FRC sets the UK Corporate Governance and Stewardship Codes and UK standards for accounting and actuarial work; monitors and takes action to promote the quality of corporate reporting; and operates independent enforcement arrangements for accountants and actuaries. As the Competent Authority for audit in the UK the FRC sets auditing and ethical standards and monitors and enforces audit quality.

© The Financial Reporting Council Limited 2022 The Financial Reporting Council Limited is a company limited by guarantee. Registered in England number 2486368. Registered Office: 8th Floor, 125 London Wall, London EC2Y 5AS

Issues with the Financial Conduct Authority

1. The director of the Financial Conduct Authority, Sophie Hutcherson, is committing cloned individual fraud.

Sophie Hutcherson, director of The Financial Conduct Authority, records the following interests in the Register of Interest: Non-Executive Director Bellecapital UK Limited 2022; Non-Executive Director Two Lyons Consulting Ltd 2022, Senior Advisor Wells Fargo Bank International 2020 2021 Senior Advisor Wells Fargo Bank 2020 2021 (Directorships and other positions (fca.org.uk))

A search in Companies House on her name returns 5 identities registered in Companies House with the same name and date of birth, which compromises the audits of all of her interests. Further analysis is described SOCIETY OF GENEALOGISTS(THE) and FCA director Sophie Hutcherson has multiple identities and fails to declare all her interests.

Sophie Hutcherson fails to declare Two Lyons Property Limited and Society of Genealogists(The). Failing to declare interests is an offence.

Sophie Hutcherson’s first interests, registered in Companies House to: DB UK Bank Limited (20 September 2016 to 26 July 2018) and D B Investments (GB) Limited (23 November 2016 to 26 July 2018), presents a potential high risk of conflict of interest with the public’s best interest, and / or furthered mutual interests, through her role at the Financial Conduct Authority, Two Lyons Property Limited and / or Society of Genealogists(The).

By holding cloned identities Sophie Hutcherson has compromised operations and audits of the Financial Conduct Authority.

2. Chair of HMRC and Moneyfarm, Dame Jayne-Anne Gadhia / Ghadia

The Financial Conduct Authority’s integrity also came into question during due diligence on Dame Jayne-Anne Gadhia, also known as Ghadia, the chair of HMRC and “Moneyfarm”.

Drawing from my Due Diligence on HMRC:

Conclusion regarding Dame Jayne-Anne

Dame Jayne-Anne has established twelve identities in Companies House, one using a misspelling of her name, and she has failed to disclose all of the interests held in each of these identities(, as expanded above). Multiple identities conceal interests. If the owner fails to disclose these interests this is evidence that the identities were created with the intention of concealing interests and this is evidence of fraud by false representation (Section 2 Fraud Act 2006). Failing to register her interests is evidence of fraud by failing to disclose information (Section 3 Fraud Act 2006).

Of particular concern is that she has five active directorships that she has failed to disclose MFM INVESTMENT LTD, MFM HOLDING LTD, JAGASH LTD, GADHIAGROUP LIMITED and UNICREDIT S.P.A., which was registered with the spelling “Ghadia” instead of “Gadhia”.

She incorrectly registered her company Usnoop Limited as “Snoop” in her biography, which renders the records of Usnoop difficult to locate. This is evidence of obfuscation.

I allege that there is sufficient evidence to support that there be a police investigation into the conduct of Dame Jane-Anne relating to her registration of multiple identities and her failure to declare past and current interests, her obfuscation around Usnoop Limited, and any conflicts, or mutual, interests arising.

Dame Jayne-Anne Gadhia / Ghadia also requires further investigation for fraud by false representation, by using a different spelling of her name, fraud by failing to disclose information in her biography, and fraud by abuse of position.

From my due diligence report, HMRC and Moneyfarm Chair, Dame Jayne-Anne Gadhia, has twelve identities in Companies House. Part 2:

The Financial Conduct Authority has posted a Notice on the MFM Investment Ltd record stating that “Money Farm” is a “cloned firm”, impersonating MFM Investment Ltd (“Moneyfarm”). The FCA provides no details of the individuals involved. This is a red flag for potential money laundering and other crime.

Due diligence findings, from the same report:

The Notice within the FS record for MFM Investment Ltd, that warns that Money Farm is a clone firm and part of a scam, should refer to its record for The Money Farm Limited, rather than being an isolated record for “Money Farm”, about which no information is provided.

Considering how the FCA regulator has failed to make this simple connection presents two options:

either, the regulator is failing to do its job, which is to ensure that the ‘Clone Scam Notice’ properly identifies the correct company;

or, the regulator has turned a blind eye.

I allege that there is evidence that the Financial Conduct Authority has been either negligent in not identifying The Money Farm Limited as a clone firm of “Moneyfarm”, or complicit in concealing this fact.

Kevin Hollinrake MP, Business Minister “responsible” for Companies House

Extracts from my report Due diligence on Kevin Hollinrake, MP responsible for Companies House.

Kevin Hollinrake MP’s directorships, as registered in Companies House, compared to his Parliamentary Register of Interests, from his election in 2015 to 30 October 2023. Red is used for interests that have not been declared in the sample of Registers of Interests examined.

Kevin Hollinrake has failed to register his directorships, when they were current, held in: identity 1, Industry and Parliamentary Trust; identity 2, Hollinrake Fielding Limited; identity 3, Agreed Online Ltd; and, identity 4, North East Yorkshire World Cup Cricket Legacy. Kevin Hollinrake has 20 appointments associated to identity 5, eighteen of which have been active whilst he has been an MP. He registered only one interest correctly, Shoptility Limited. He initially failed to register Sortit Ltd, on 7 July 2017 and 18 July 2018, declaring it correctly on 12 August 1019. He registered Hunters Group Limited, on 3 June 2015, but he failed to register this directorship in the following five years. He failed to register his directorship of Hunters Property PLC on 3 June 2015 and correctly registered it in the following six years.

Kevin Hollinrake failed to register his directorships of a further thirteen companies, registered to identity 5: Herriot Cottages Limited, Hunters Franchising Limited, Maddison James Limited, Hunters Partners Limited, Hapollo Limited, Realcube Technology Limited, Realcube Limited, Hunters Group Limited, Hunters Survey and Valuation Limited, Hunters (Midlands) Limited, Hunters Financial Services Limited, The Clock (Yorkshire) Limited and Millfield Court Management Limited.

Kevin Hollinrake has breached the Parliamentary Code of Conduct relating to declaring directorships. In addition, he has breached the Companies Act 2006, the Fraud Act 2006 and Anti-Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing legislation. The risk to the public’s best interest is high because his breaches put the public at risk that he is involved in money laundering and terrorism financing.

The outcome of an individual holding multiple identities, is to conceal interests, from audits and due diligence, that ought to be visible. Registering multiple identities can be accidental, but, if the individual fails to register all of their appointments in each of the identities, this is evidence that the additional identities were created deliberately to conceal interests.

Kevin Hollinrake has registered five identities in Companies House and failed to register the interests appointed to four of these identities. This is evidence that these identities were each created with the intention of concealing the interest appointed to that identity, from his interests held in other identities.

Directors confirm relevant audit information is disclosed as per Section 418 of the Companies Act 2006.

418Contents of directors' report: statement as to disclosure to auditors

(1)This section applies to a company unless—

(a)it is exempt for the financial year in question from the requirements of Part 16 as to audit of accounts, and

(b)the directors take advantage of that exemption.

(2)The directors' report must contain a statement to the effect that, in the case of each of the persons who are directors at the time the report is approved—

(a)so far as the director is aware, there is no relevant audit information of which the company's auditor is unaware, and

(b)he has taken all the steps that he ought to have taken as a director in order to make himself aware of any relevant audit information and to establish that the company's auditor is aware of that information.

(3)“Relevant audit information” means information needed by the company's auditor in connection with preparing his report.

(4)A director is regarded as having taken all the steps that he ought to have taken as a director in order to do the things mentioned in subsection (2)(b) if he has—

(a)made such enquiries of his fellow directors and of the company's auditors for that purpose, and

(b)taken such other steps (if any) for that purpose, as are required by his duty as a director of the company to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence.

(5)Where a directors' report containing the statement required by this section is approved but the statement is false, every director of the company who—

(a)knew that the statement was false, or was reckless as to whether it was false, and

(b)failed to take reasonable steps to prevent the report from being approved, commits an offence.

(6)A person guilty of an offence under subsection (5) is liable—

(a)on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or a fine (or both);

(b)on summary conviction—

(i)in England and Wales, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding twelve months or to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (or both);

(ii)in Scotland or Northern Ireland, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months, or to a fine not exceeding the statutory maximum (or both).

How section 418 relates to a person who has failed to disclose interests held in synthetic identities.

Section 418 of the Companies Act 2006 pertains to the contents of directors' reports and includes a statement concerning disclosure to auditors. Here's a summary of how it relates to a person who has failed to disclose interests held in synthetic identities:

Statement Requirement:

Section 418 requires the directors' report to contain a statement for each director, confirming that, to the best of their knowledge, there is no relevant audit information of which the company's auditor is unaware.

The statement must affirm that the director has taken all necessary steps to be aware of any relevant audit information and to ensure the auditor is also aware of it.

Relevant Audit Information:

"Relevant audit information" refers to information needed by the company's auditor in connection with preparing the audit report.

Duty of Directors:

Directors are obligated to take all necessary steps to make themselves aware of any relevant audit information.

This includes making inquiries of fellow directors and the company's auditors and taking other steps required by their duty to exercise reasonable care, skill, and diligence.

Consequences of False Statement:

If the statement in the directors' report is false, and a director knew it was false or was reckless, and failed to prevent the report's approval, it is considered an offense.

The offense can lead to criminal liability with potential imprisonment and/or fines, depending on the severity and jurisdiction.

In the context of synthetic identities and undisclosed interests, a failure to disclose such information could be relevant audit information. If a director knowingly fails to disclose interests held in synthetic identities, it may lead to a false statement in the directors' report. This failure could result in legal consequences, including criminal charges and associated penalties as outlined in Section 418.

Financial Conduct Authority on Disclosure of Interests for listed companies

The Financial Conduct Authority Handbook sets out guidance on disclosure of directors interests in the Annual financial report, in section LR 9.8.6 (LR 9.8 Annual financial report - FCA Handbook):

LR 9.8.6. In the case of a listed company incorporated in the United Kingdom, the following additional items must be included in its annual financial report:

(1) a statement setting out all the interests (in respect of which transactions are notifiable to the company under article 19 of the Market Abuse Regulation) of each person who is a director of the listed company as at the end of the period under review including:

(a) all changes in the interests of each director that have occurred between the end of the period under review and a date not more than one month prior to the date of the notice of the annual general meeting; or

(b) if there have been no changes in the period described in paragraph (a), a statement that there have been no changes in the interests of each director.

Interests of each director includes the interests of connected persons of which the listed company is, or ought upon reasonable enquiry to become, aware. (LR 9.8 Annual financial report - FCA Handbook)

It is crucial to note that the Financial Conduct Authority Handbook, section LR9.8.6, mandates the inclusion of a statement in the annual financial report outlining all interests of each director, including changes in these interests. This includes interests of connected persons that the listed company is, or ought upon reasonable inquiry to become, aware of.

Companies Act and unique identities

The Companies Act 2006 has recently been amended by the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023. Section 1082 Allocation of unique identifiers, states:

1082 Allocation of unique identifiers

(1)The Secretary of State may [F1by regulations] make provision for the use, in connection with the register [F2or dealings with the registrar], of reference numbers (“unique identifiers”) to identify each person who—

(a)is a director of a company,

(b)is secretary (or a joint secretary) of a company,

[F3(ba)is an authorised corporate service provider;

(bb)is an individual whose identity is verified,] or

(c)in the case of an overseas company whose particulars are registered under section 1046, holds any such position as may be specified for the purposes of this section by regulations under that section.

(2)The regulations may—

(a)provide that a unique identifier may be in such form, consisting of one or more sequences of letters or numbers, as the registrar may from time to time determine;

(b)make provision for the allocation of unique identifiers by the registrar;

(c)require there to be included, in any specified description of documents delivered to the registrar, as well as [F4a statement of the person's name] [F4any statement by or referring to the person]—

(i)a statement of the person's unique identifier, or

(ii)a statement that the person has not been allocated a unique identifier;

[F5(d)enable the registrar to take steps where a person appears to have more than one unique identifier to discontinue the use of all but one of them.]

[F5(d)confer power on the registrar—

(i)to give a person a new unique identifier;

(ii)to discontinue the use of a unique identifier for a person who is allocated a new identifier or who has more than one.]

(3)The regulations may contain provision for the application of the scheme in relation to persons appointed, and documents registered, before the commencement of this Act.

(4)The regulations may make different provision for different descriptions of person and different descriptions of document.

(5)Regulations under this section are subject to affirmative resolution procedure.

Textual Amendments

F1Words in s. 1082(1) inserted (26.10.2023 for specified purposes) by Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (c. 56), ss. 68(2)(a)(i), 219(1)(2)(b)

F2Words in s. 1082(1) inserted (26.10.2023 for specified purposes) by Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (c. 56), ss. 68(2)(a)(ii), 219(1)(2)(b)

F3S. 1082(1)(ba)(bb) inserted (26.10.2023 for specified purposes) by Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (c. 56), ss. 68(2)(a)(iii), 219(1)(2)(b)

F4Words in s. 1082(2)(c) substituted (26.10.2023 for specified purposes) by Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (c. 56), ss. 68(2)(b), 219(1)(2)(b)

F5S. 1082(2)(d) substituted (26.10.2023 for specified purposes) by Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (c. 56), ss. 68(2)(c), 219(1)(2)(b)

The amendments to Section 1082 of the Companies Act 2006, as stipulated in the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act of 2023, introduce pivotal alterations concerning the unique identifiers attributed to individuals occupying specific roles within companies.

Legitimacy of Holding Multiple Identifiers:

These amendments underscore the imperative for an individual to possess a solitary unique identifier. This is conspicuously evident in the provision empowering the registrar to cease the utilisation of multiple identifiers for a person.

Reinforcement of Regulatory Framework:

The amendments serve to fortify the regulatory framework governing unique identifiers, explicitly asserting that an individual must not be associated with more than one unique identifier.

Request for Register of Interests:

My complaints regarding the concurrent use of multiple identities is akin to maintaining numerous unique identifiers. The amendments to Section 1082 elucidate that possessing multiple identifiers is incongruent with established regulatory norms.

Legal Grounds:

These amendments provide a firm legal foundation for my contention that individuals, particularly those in directorial and secretarial positions, should refrain from assuming multiple unique identifiers.

Cautionary Note:

It is crucial to note that the current state of legislation, as embodied in Section 1082, may necessitate complementary measures to ensure the ongoing integrity of financial statements and the effective tracing of changes. Presently, there is no provision within the legislation for these essential components, which poses a potential risk to the thoroughness of financial reporting and change tracking. This requires urgent attention to safeguard against potential loopholes in regulatory oversight.

Cloned Individuals terminology

Linguistically, the term “cloned individuals” could apply when an individual has created clone identities of themselves. This also describes the situation where an individuals purports to be multiple individuals in Companies House, by using variations of their attributes (name, date of birth or usual residential address).

Since, multiple identities in Companies House conceals the interest(s) from auditors, due diligence and “Know your customer” checks, self-cloned individuals fundamentally breach our systems of governance and accountability.

I propose the following definition:

A cloned individual can be:

either, an imposter, a person who is impersonating another individual by using someone else’s personal details, or,

or, a person with synthetic identities, who purports to be multiple individuals, by using variations of their own personal details. For example, by registering multiple identities in Companies House with different names, date of birth or usual residential address. This is as a “self-cloned”.

Examples of the scams that cloned firms and cloned individuals can perpetrate:

Clone firm, registered by an unrelated third party, to defraud by impersonation (as per the FCA and Action Fraud examples);

Clone firm fraud by a related party of the legitimate firm eg to enable a second bank account under the control of the directors which remains “off the balance sheet”;

Cloned individual, concealing mutual interests from auditors and HMRC;

Cloned individual with clone firm, to launder money from the mutual firm to avoid tax and dividend payments. This can be perpetrated alone, in collusion with other directors and / or the auditor, and / or, as part of a cartel. Cartels have been concealed from accountants and auditors by the use of clone identities.

The benefit of multiple identities, to a criminal.

The benefit of having multiple identities, to a criminal, is that it enables the individual to conceal interests held in other identities from audits, Know Your Customer and Know Your Supplier due diligence.

The purpose of concealing interests to enable fraud.

The purpose of concealing interests is to enable fraudulent transactions that are ‘related party’ transactions with mutual interests, this can involve money-laundering, people trafficking and terrorism financing. Transactions that, otherwise, would have been flagged or stopped by the accountability controls, are allowed incorrectly to proceed. That is, if all an individual’s interests were held in one identity, transactions that have been authorised, would have been flagged as a related party transaction and prevented from occurring. Transactions incorrectly enabled have a material impact on the firm’s financial statements and public security.

My due diligence reports lead to the conclusion that cloned individual and cloned firm fraud is a prolific method of director-led fraud, that has been being used undetected for centuries. It is common amongst members of Parliament, the House of Lords and active businesses. The full extent of its cost to society is likely to exceed Thomson Reuters’ estimate of $20 to $40 billion per annum, Trends in synthetic identity fraud.

Conclusion

Thomson Reuters estimates annual losses of $20 to $40 billion due to synthetic identity fraud, a method steadily on the rise. Cabinet Office and Government Digital Services define synthetic identities as either fictional or based on real identities. The creation of multiple identities in Companies House, altering details such as names, dates of birth, or addresses, aligns with this definition, posing a significant risk, which is a breach of Section 1082 which requires an individual to have a single unique identifier.

Companies House acknowledges its authority to merge duplicate records but seemingly lacks a proactive approach. The National Cyber Security Centre underscores the importance of unique identities for cybersecurity, urging systems operators like Companies House to minimize errors and maintain a zero-trust architecture.

While the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) recognizes "clone individuals," its focus on "clone firm" fraud overlooks directors committing fraud on their legitimate firms using cloned identities, a gap mirrored in Action Fraud and City of London Police documentation.

Auditing standards, such as ISA 240 (UK), lack explicit consideration of keywords associated with synthetic identity fraud and cloned company fraud. This oversight hampers the identification of undisclosed interests, leading to material misstatements in financial reporting.

The inconsistency in law enforcement guidance, fixated on imposter fraud, neglects to comprehensively address synthetic identity fraud and cloned company fraud. This gap hinders individuals attempting to report such cases, as reporting systems like Action Fraud are not tailored to accommodate these nuances, risking breaches in anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism, and cybersecurity legislation.

To bolster fraud recognition and reporting mechanisms, it is imperative to expand law enforcement guidance, auditing protocols, and reporting systems to explicitly address synthetic identity fraud and cloned company fraud, thereby fortifying efforts against evolving fraudulent practices.